Note: this post will contain spoilers for Birthplace of Ossian by Connor Sherlock. You really ought to go play it before you read this, it’s free and isn’t all that long.

Birthplace of Ossian by Connor Sherlock belongs to one of my favorite genres of games: quiet walking simulators which don’t try to tell you some specific story, but exist as a sort of massive 3D sculpture for you to wander around in; until you get bored and decide that you’ve seen enough. Birthplace of Ossian is excellent for this, consisting of 100 square kilometers of fictional Scottish highlands to explore and meander through.

Ossian was a fictional ancient Irish/Scottish poet who had large bodies of poetry supposedly collected and translated into English by Scottish poet James Macpherson in the 18th century. To tell an abbreviated version of events for the purposes of talking about this game, Macpherson wrote the poetry in English himself, and passed it off as translations from ancient Gaelic. It became wildly popular, and had a tremendous influence on the Romantic movement in the first half of the 19th century. Goethe even has Werther in The Sorrows of Young Werther reading a translation. Eventually though, people started really asking for the Gaelic originals, and the deception was discovered.

A solid overview of this history is in an article which Sherlock quotes on the Itch page for Birthplace of Ossian, Ossian in Painting (1947) by Henry Okun. As is implied by the title, the character of Ossian himself, as well as a variety of scenes from the poems, became exceptionally popular subjects for painting throughout the 19th century.

Many of these paintings took very direct inspiration from Greek and Roman sources, especially Homer, as well as from Biblical scenes.

Ossian was often depicted as an Irish or Scottish incarnation of Homer, or the two were sometimes depicted together. He was also blind and was depicted with a flowing white beard.

This, in a fortuitous coincidence, thematically matched up to the original project of James Macpherson; much of his poetry that was supposedly written by Ossian also takes direct inspiration from the Bible and from classical literature, again mostly from Homer.

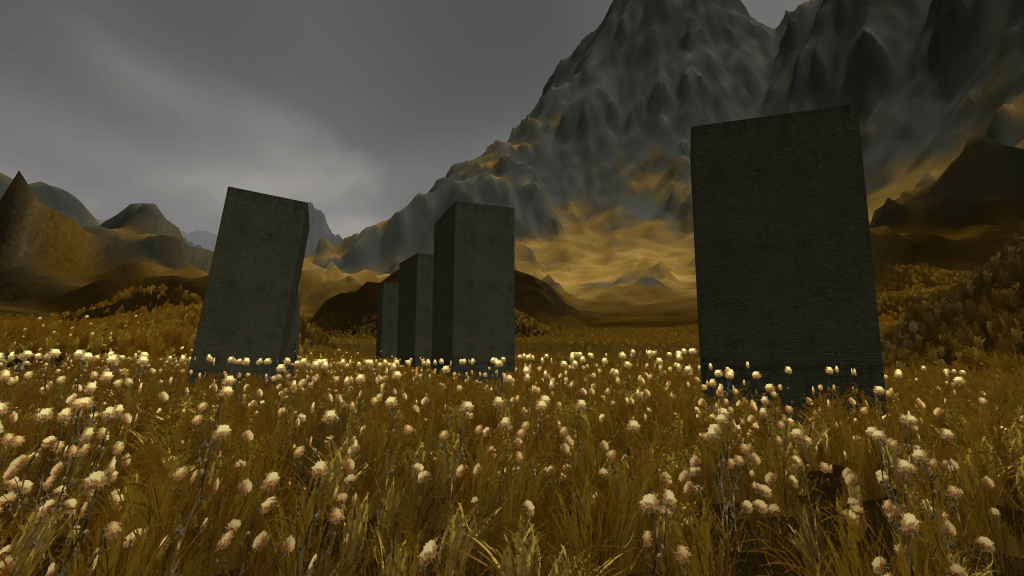

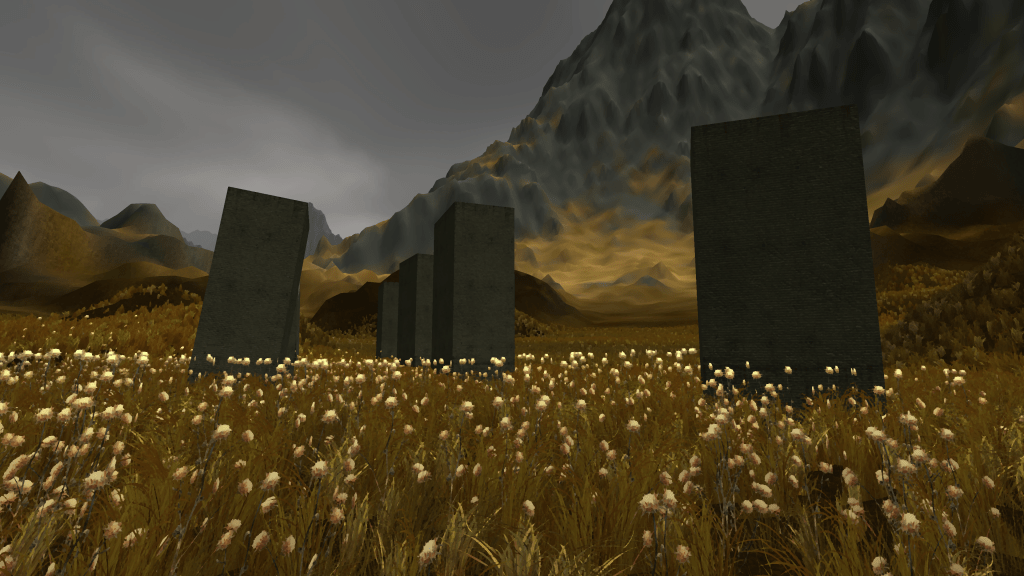

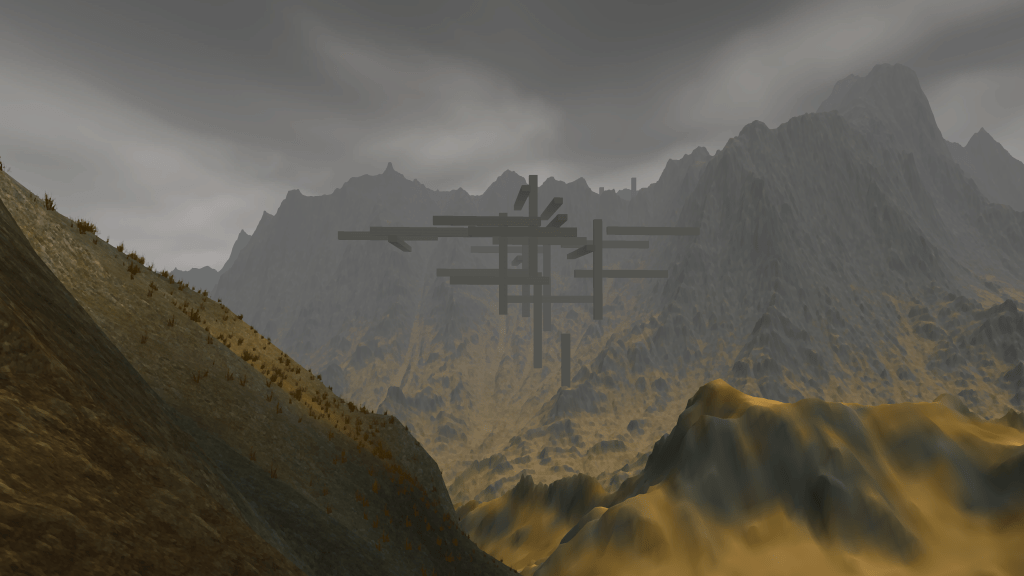

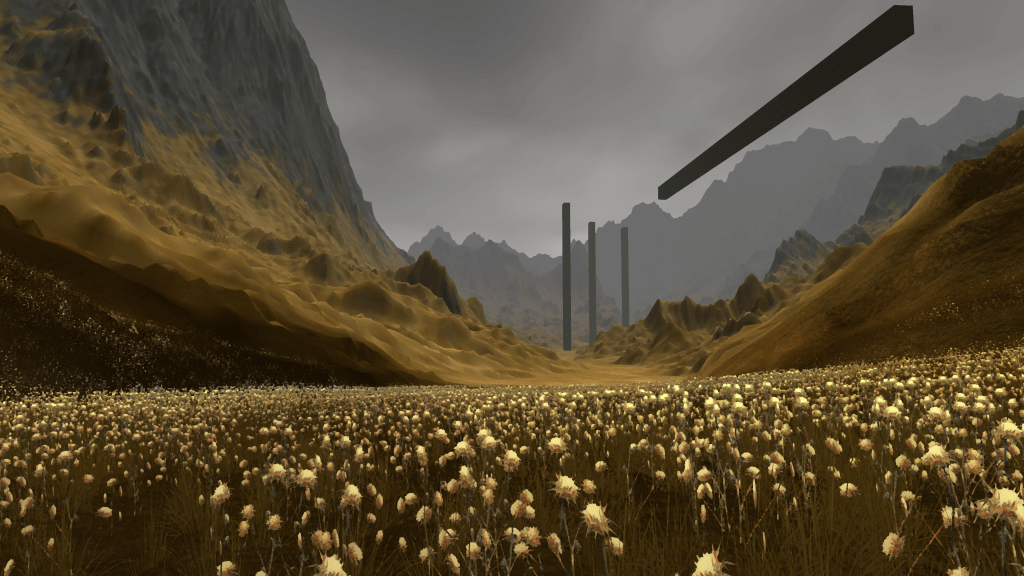

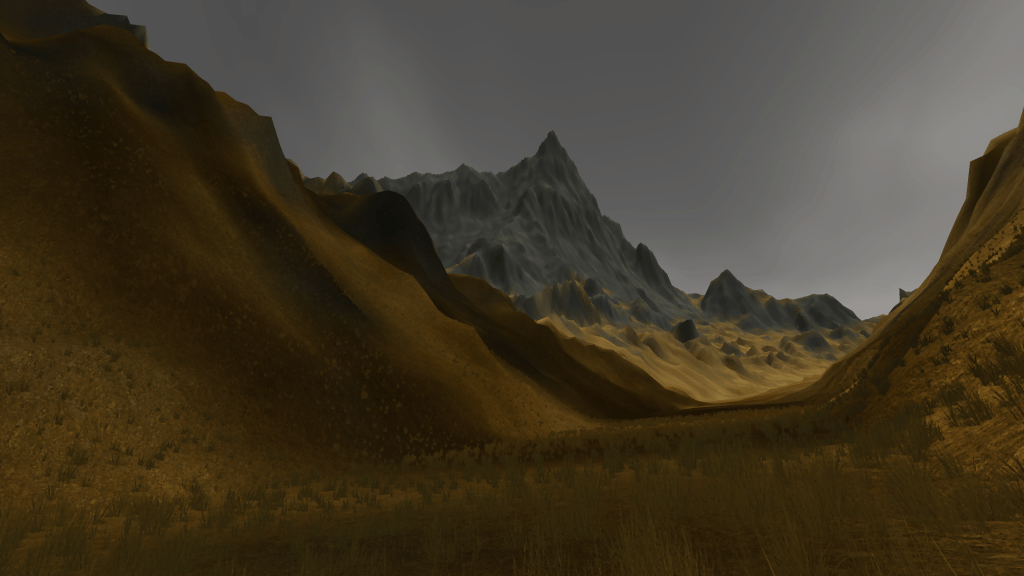

Birthplace of Ossian exists uncomfortably in the center of this same tension between the authentically natural and the constructed. The game starts you off by dropping you into a rough and broken circle of standing stones in a hyper-exaggerated version of the Scottish Highlands. (While Ossian is based on the Irish folk character of Oisín, Macpherson recast him a Homeric bard in his native Scotland.) Your first view is of a contrast between towering mountains and perfectly squared off slabs of stone, carved by human hands (the screenshot above). Looming on a hill above nearby, over a field of flowers, another standing stone sits silhouetted.

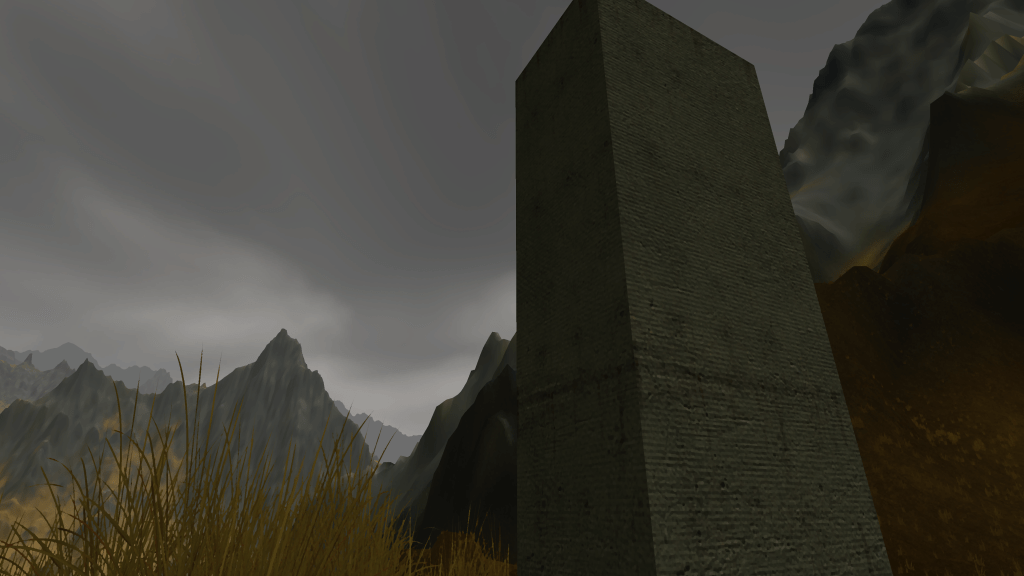

However, when you approach, the stone is not some ancient carved bluestone slab, sanded down by millennia of the wind that dominates the game’s soundscape. Instead, it is a deceptively modern construction, made from reinforced concrete with subtly visible steel rebar. Like the modern construction of Macpherson’s Ossian, the rock is only pretending at antiquity.

A droning music also fills in the gaps between the wind (Connor Sherlock is also a prolific composer), bearing the same tension. Although composed of distorted synths, you can almost hear the ringing of the harp that Ossian supposedly played his epics on, in digital facsimile.

As you go, you see more and more standing stones, seemingly too square and just a little too big to be easily likened to a British standing stone.

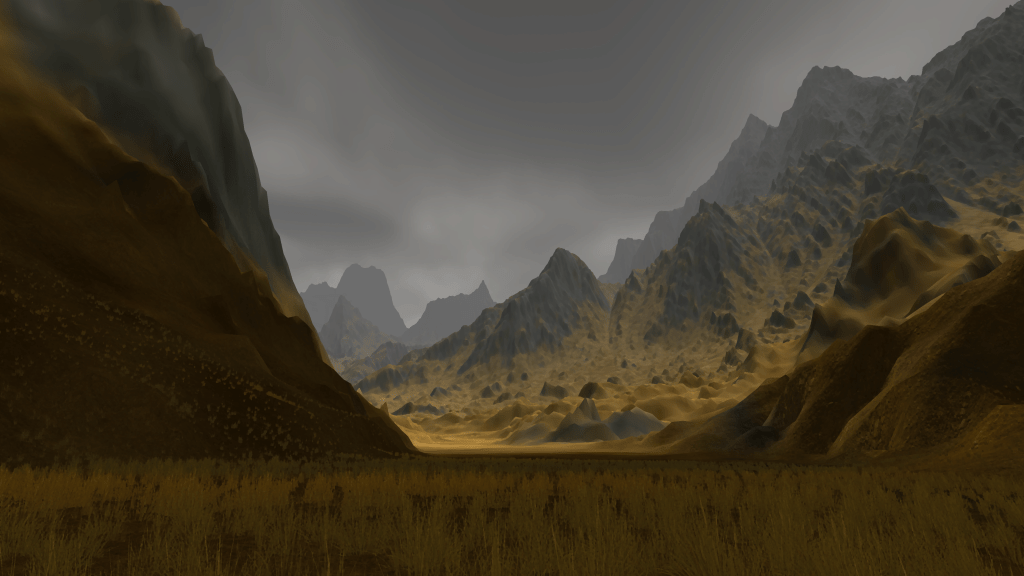

Deeper in to the seemly unending peaks, you spot more right angled standing stones peeking over a curved and natural mountainside. After a long and bumpy trek to get around the edge and see what’s there, the view hits like a punch in the mouth:

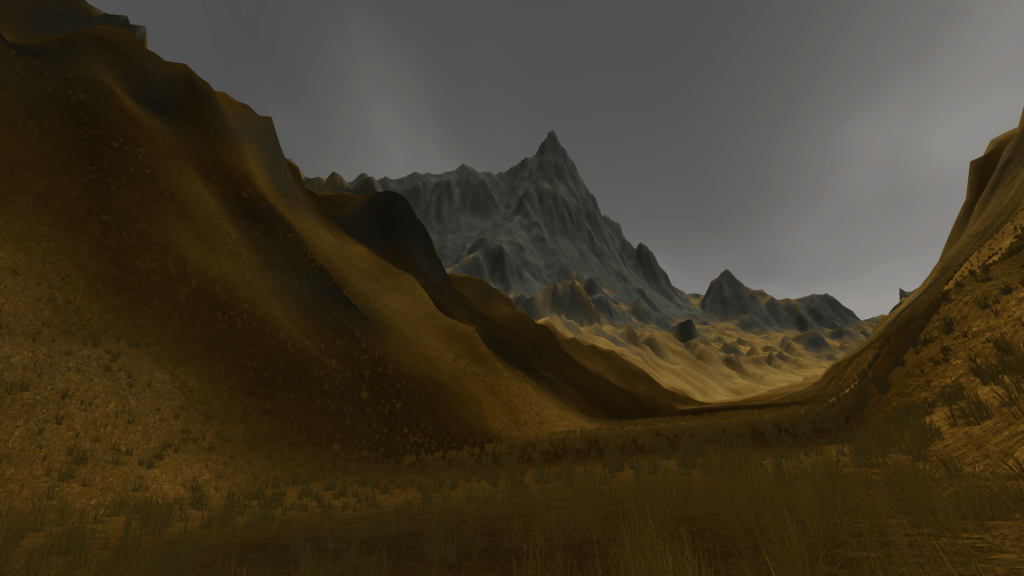

Suddenly the landscape around seems to unravel, and you realize that its not just the rocks that are an artificial construction, the entire mountainous landscape is hewn from ones and zeros, a not even really realistic depiction of the Scottish highlands. The idea of the actual birthplace of Ossian may have been a construction of James Macpherson, but this is a digital reconstruction of a romantic idea imagining that original facsimile.

Even the mountains themselves hint at this, being more akin to an imitation of the neoclassical and romantic paintings of Ossian’s world than an imitation of the world of the actual poetry that Macpherson penned in English. They seem to swim with literal brushstrokes.

The white flowers and grass which fill the foreground, on the other hand, are rendered, if not realistically, then more realistically. They don’t seem to have the same sort of painterly majesty that the mountains tower over you with.

Due to the way that Birthplace of Ossian is rendered, though, there is a awkward middle distance which is always present. A transitional zone between the painterly mountains and the photo-realism of the plants in front of you grows and shrinks as you walk.

This rough-hewn band seems almost from an earlier digital age; the unformed binary stuff that both the mountains and the grass and the alien monoliths are carved from. It sits in the tense space between them all, a visible reminder of the sharp stretch between the reality and the artifice that exists in your suspension of disbelief when you play any video game, or that all those painters might have recognized in the works of James Macpherson.

If you liked the raw visuals, the droning synth music, or the themes exploring the tension between the natural and the man-made present in Birthplace of Ossian, these all exist in great abundance in the rest of Connor Sherlock’s work. This game serves as an excellent introduction to that body of work; if you are looking for a place to start, his Walking Simulator of the Month bundles are excellent, and at the time of writing, are on sale for ludicrously cheap. If you were just going to get one, I would recommend Far Future Tourism.